Why This Unassuming Seed Changed Human History

Close your eyes and imagine a scent that transported emperors, sparked wars between nations, and once commanded prices higher than gold itself. That aroma is nutmeg a spice so historically significant that entire colonial empires rose and fell fighting over the tiny Banda Islands where it grows. Yet today, most home cooks treat nutmeg as a background player, reserved for autumn desserts and holiday beverages. This is a profound culinary mistake.

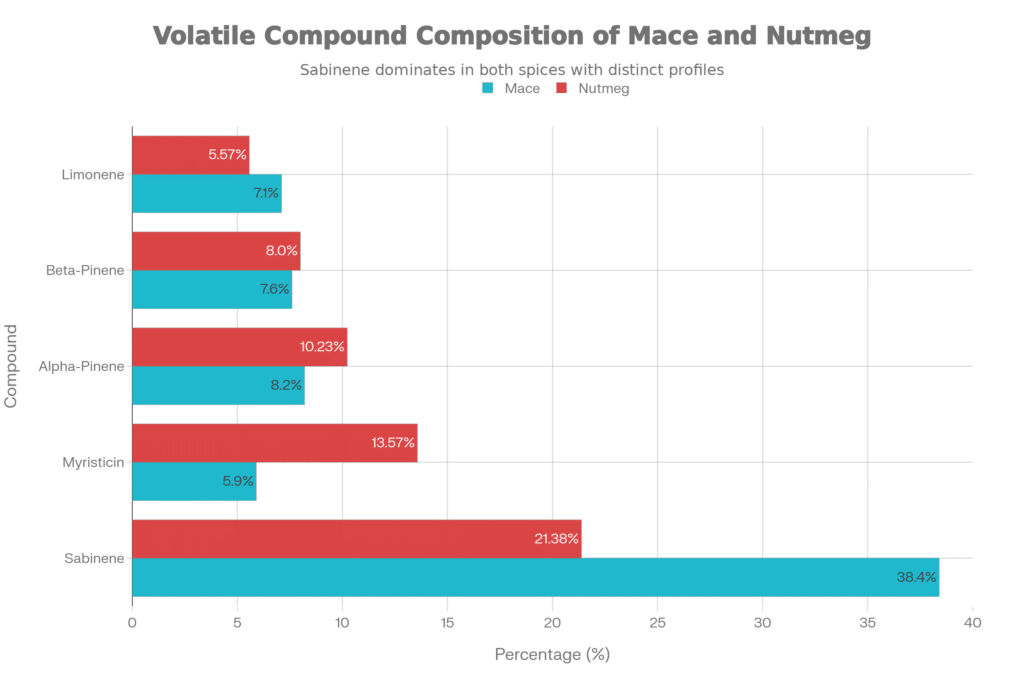

Nutmeg is not a seasonal spice but a transformative ingredient that bridges sweet and savory, traditional and innovative, simple and sophisticated. Within this single brown seed lies 21.38% sabinene, 13.92% terpineol, and 13.57% myristicin—compounds that create warmth, earthiness, and aromatic complexity unmatched by any other common spice. Whether you’re a home cook seeking to elevate everyday dishes or a professional chef wanting to deepen your repertoire, understanding nutmeg’s chemistry, history, culinary applications, and mastery techniques will fundamentally transform your cooking. This is the complete guide to becoming a nutmeg master.

THE HISTORY: From Banda Islands to Global Treasure

Nutmeg’s story is colonial history distilled into a single spice. For thousands of years, nutmeg existed only in the Banda Islands—a remote Indonesian archipelago where Portuguese explorers arrived in 1511 to discover what Europeans had only heard whispered in legend. The Dutch East India Company built a monopoly so ruthless that they committed genocide, reducing the islands’ population from 15,000 to 1,000, and enslaved survivors to cultivate plantations.

This monopoly lasted nearly 200 years until British botanists stole nutmeg trees and transplanted them to Sri Lanka, Penang, and ultimately Grenada, where the spice became so central to the island’s identity that it now appears on the national flag. From this brutal history emerged one of the world’s most valuable and beloved spices, today cultivated across Indonesia, Grenada, India, and Sri Lanka, accessible to every kitchen yet still commanding respect from serious cooks.

THE CHEMISTRY: Understanding Why Nutmeg Tastes and Feels the Way It Does

To truly master nutmeg in the kitchen, one must understand its chemistry. The spice’s essential oil—which comprises 6.85% of the dried seed by weight—consists of a complex mixture of volatile compounds that interact synergistically to create the warm, earthy, slightly sweet profile that cooks recognize instantly.

The dominant volatile compound is sabinene (21.38%), a monoterpene that contributes woody, spicy, peppery notes and structural warmth. The second-most abundant is 4-terpineol (13.92%), which adds sweet, herbal, slightly floral undertones that balance sabinene’s sharpness. Myristicin (13.57%), the signature compound often associated with nutmeg’s identity, is an allylic benzodioxole that creates the spice’s distinctive warm, slightly numbing sensation on the palate—the same compound responsible for nutmeg’s traditional reputation as a toothache remedy.

Other important compounds include α-pinene (10.23%), which adds bright, pine-like freshness, and limonene (5.57%), which contributes subtle citrus character. Safrole (4.28%), a benzodioxole compound chemically similar to myristicin, is naturally present at low levels and is responsible for some of nutmeg’s anise-like character. Eugenol (also present in cloves and cinnamon) adds warm, clove-like notes. Elemicin (1.42%) is a hallucinogenic compound naturally present in minute quantities that has minimal effect at normal culinary doses but becomes significant if nutmeg is consumed in excessive amounts.

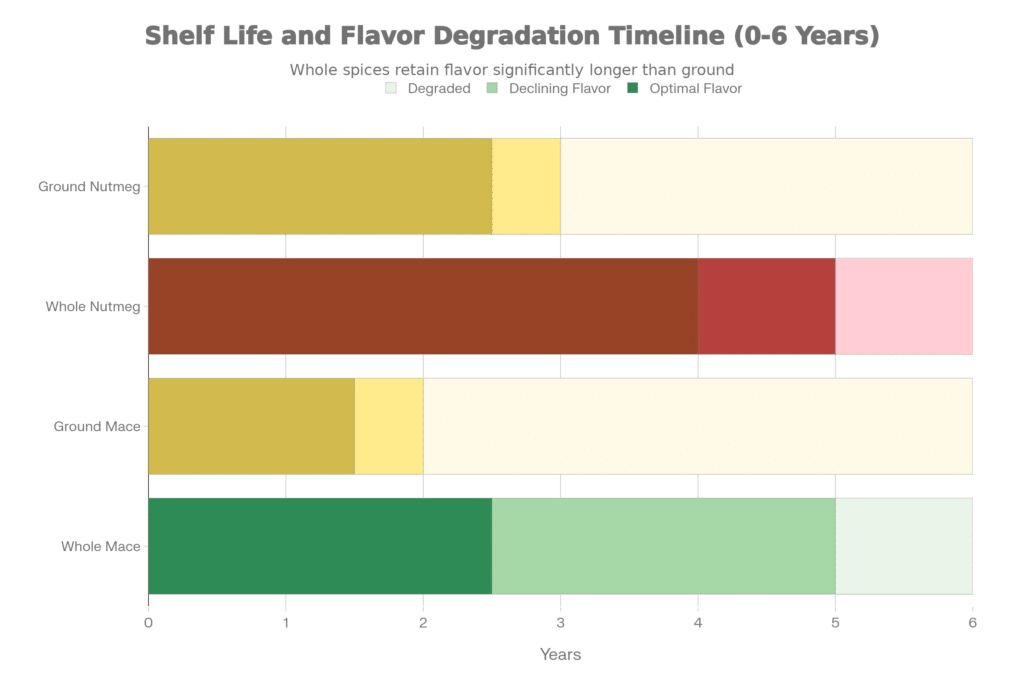

The chemistry changes dramatically depending on processing. Whole nutmeg seeds maintain their complex aromatic profile because volatile oils are protected by the hard seed coat. When nutmeg is ground, the dramatically increased surface area means oils oxidize rapidly upon exposure to air and light—this is why freshly ground nutmeg delivers 3 times stronger aroma and 25% deeper flavor penetration than pre-ground nutmeg stored in jars.

Toasting adds another chemical dimension. When whole nutmeg seeds are exposed to 160°C (320°F) heat for 2-5 minutes, Maillard reactions occur—the same chemical process that browns meat during searing. These reactions create new aromatic compounds that enhance sweetness and warmth while reducing the sharp, slightly medicinal notes of raw nutmeg. This is why toasted-then-ground nutmeg delivers restaurant-quality complexity unavailable in pre-toasted, pre-ground commercial products.

FLAVOR PROFILE DECODED: The Sensory Experience of Nutmeg

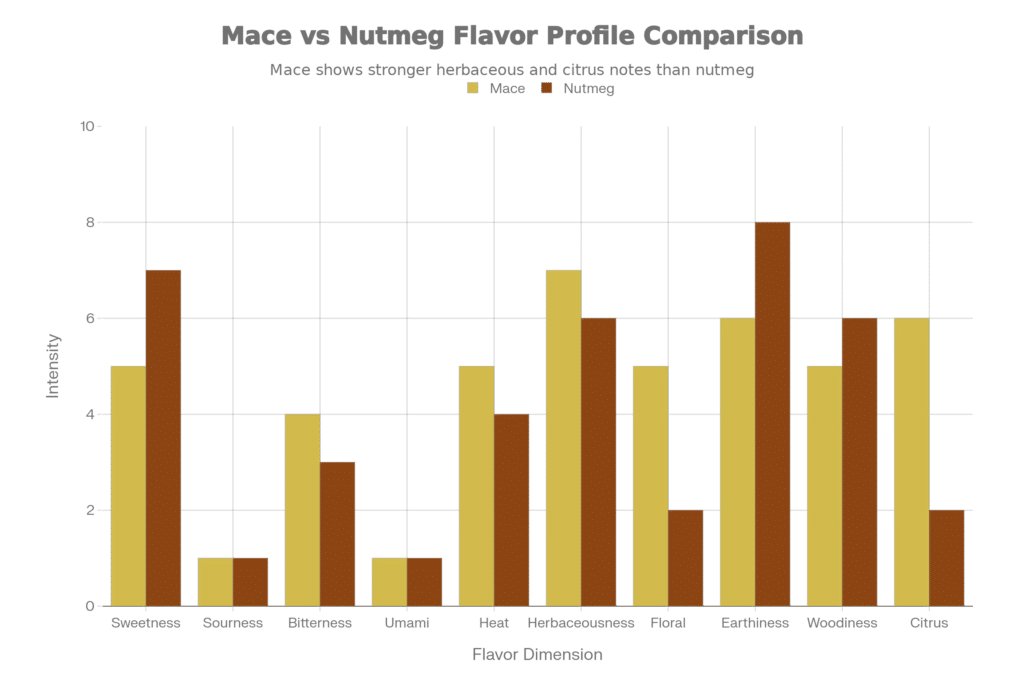

Nutmeg’s flavor profile divides into distinct dimensions that explain why it’s equally at home in pumpkin pie and creamed spinach. The dominant characteristic is earthiness (8/10)—a deep, grounded mineral quality that comes from sabinene and other woody compounds. This earthiness creates a sensation of substance and warmth. Sweetness (7/10) emerges as the second major note, arising from 4-terpineol and the spice’s natural sugars, creating a perception of richness without requiring added sugar. Unlike cloves (which register 8/10 heat) or cinnamon (which emphasizes 8/10 sweetness), nutmeg balances sweetness with earthiness, creating equilibrium.

Herbaceousness (6/10) adds garden-like complexity—the sensation that you’re tasting something aromatic and slightly botanical. This prevents nutmeg from becoming overly sweet or flat. Woodiness (6/10) provides structural support, creating the sensation of warmth and substance that pairs naturally with both cream-based and spiced applications. Heat (4/10) registers as moderate—not aggressive like black pepper, but present enough to create the sensation of warmth (this comes from myristicin’s natural numbing property and the peppery notes of sabinene).

Bitterness (3/10) emerges subtly as tannin-driven drying, preventing the spice from becoming cloying. Notably, nutmeg contains virtually no sourness (1/10), virtually no umami (1/10), minimal floral character (2/10), and almost no citrus notes (2/10) despite α-pinene’s presence. This sensory profile explains why nutmeg’s natural partners are sweetness (apples, sugar, honey), fat (cream, butter, cheese), and umami-free vegetables (spinach, potato, carrots) rather than acidic or savory-first ingredients.

CULINARY MASTERY: From Ancient Technique to Modern Innovation

Nutmeg’s versatility is extraordinary—it appears in more diverse applications than almost any other single spice. Mastering it requires understanding when to deploy whole versus ground, how to maximize freshness, and where this spice truly transforms dishes.

Whole Nutmeg: The Long Infusion Approach

Whole nutmeg seeds, protected by their hard shell, maintain volatile oils indefinitely and can be grated fresh moments before serving. This form excels in applications where the spice infuses slowly into liquids over extended cooking—custards that bake for 45 minutes, creamy sauces simmered for 20 minutes, or soups prepared over an hour. The slow release of aromatic oils creates integrated warmth rather than harsh front-and-center spice character.

For sweet applications, whole nutmeg grated fresh into custard, pumpkin pie filling, or apple crumble delivers aroma that pre-ground cannot match. The microplane grater (favored by professional chefs) or dedicated nutmeg grater creates fine texture impossible with coarser grinding tools. Grate directly over the warm dish moments before serving when possible to maximize aroma.

For savory applications, whole nutmeg shaved into béchamel sauce creates a classic French preparation that forms the base of lasagna, moussaka, gratins, and cauliflower gratin. The sauce simmers gently, allowing the nutmeg’s earthiness to integrate completely while the cream’s fat distributes its flavors evenly. Mashed potatoes—a seemingly simple dish—become elevated when freshly grated nutmeg is stirred in at the moment of serving, creating an aromatic burst that transforms the vegetable’s earthiness.

Ground Nutmeg: Strategic Application in Spice Blends and Dry Rubs

Ground nutmeg serves different purposes than whole. Because it distributes throughout dishes as fine particles, it works best in applications requiring even spice distribution: baked goods, spice blends, dry rubs for meat, and preparations where whole seeds would be impractical.

In baking, ground nutmeg combines with cinnamon, allspice, and ginger in spice cake, gingerbread, and apple pie applications. The warmth complements sweetness without overwhelming delicate flour structures. For optimal results, purchase whole nutmeg, freeze for 10 minutes to prevent grinding oils from becoming paste, then grind fresh with a dedicated spice grinder (not a blender, which creates uneven inconsistency). Fresh-ground maintains maximum aroma for approximately 24 hours, then degrades at 20% per 72 hours.

In savory spice blends, ground nutmeg appears in Indian garam masala (creating warmth to balance spicy heat), Middle Eastern meat rubs (adding complexity to lamb and beef), and Italian sausage mixtures (enhancing proteins with warmth and earthiness). The key is using ground nutmeg in blends that will be cooked immediately, not stored for extended periods—pre-blended nutmeg loses character rapidly.

The Blooming Technique: Maximum Distribution with Minimum Waste

Professional cooks employ a technique called “blooming” for maximum nutmeg effect in cooked dishes. Rather than adding ground nutmeg directly to food, warm butter, oil, or ghee in a heated pan, add the measured ground nutmeg, stir constantly for 30-60 seconds, then immediately add remaining ingredients. This brief heating activates the spice’s essential oils while dispersing them into the fat, ensuring even distribution throughout the dish and preventing bitter, overly concentrated flavor patches.

This technique works exceptionally well for cream-based pasta sauces, soups requiring spiced flavor integration, and savory meat dishes where raw spice powder might remain unpleasantly gritty.

The Toasting Transformation: From Good to Extraordinary

The single greatest technique for elevating nutmeg-based preparations is toasting whole seeds before grinding. This simple 5-minute process delivers flavor improvements discernible to untrained palates. Place whole nutmeg seeds in a dry skillet over medium heat, stir constantly for 2-5 minutes until the seeds become slightly darker and release an intense, sweet aroma. Immediately transfer to a cool plate to halt the cooking process.

Once cooled, freeze the toasted seeds for 10 minutes (this prevents grinding oils from becoming paste), then grind using a mortar and pestle or dedicated spice grinder. The resulting powder will demonstrate noticeably deeper warmth, enhanced sweetness, and more caramel-like complexity than pre-ground commercial nutmeg. This technique transforms simple preparations—a basic custard becomes a restaurant-quality experience, mashed potatoes develop unexpected complexity, and spiced cakes achieve depth that pre-ground cannot deliver.

PAIRING SCIENCE: Creating Harmonious Dishes with Nutmeg

Nutmeg’s earthiness and sweetness create specific pairing logic that distinguishes successful applications from awkward ones.

Sweet Pairings:

Nutmeg’s 7/10 sweetness complements sugary ingredients naturally. Apples (both tartness and sweetness), pears, stone fruits, honey, brown sugar, molasses, and maple syrup all amplify nutmeg’s aromatic warmth. This partnership explains why apple pie, pumpkin pie, and spiced cakes featuring both nutmeg and sugar achieve harmony—the spice and sweetness elevate each other rather than competing.

Creamy Pairings:

The earthiness and warmth of nutmeg pair exceptionally well with cream, milk, butter, and cheese. The fat distributes aromatic oils evenly while the dairy provides richness that prevents the spice from registering as harsh. This is why béchamel sauce (made from butter, flour, and milk, finished with nutmeg) becomes a foundational French preparation—the nutmeg’s earthiness transforms a simple white sauce into something sophisticated.

Vegetable Pairings:

Nutmeg’s earthiness naturally complements earthy vegetables—potatoes, carrots, spinach, squash, and pumpkin all contain compounds that harmonize with sabinene and terpineol. These vegetables provide neutral canvases where nutmeg’s warmth becomes the star. Mashed potatoes, creamed spinach, butternut squash soup, and roasted carrot dishes all showcase how nutmeg elevates simple vegetables into memorable side dishes.

Protein Pairings:

In savory applications, nutmeg’s warmth complements rich proteins. Lamb is traditionally paired with nutmeg in Middle Eastern cooking (creating sophisticated depth), and the spice appears in Italian sausage and beef formulations. The earthiness and warmth enhance umami-rich meat flavors without overwhelming them. Fish and delicate white poultry require lighter nutmeg touches to avoid dominating subtle flavors.

Spice Pairings:

Nutmeg harmonizes beautifully with cinnamon (both are warming), allspice (which actually tastes like a blend of cinnamon, clove, and nutmeg), ginger (which adds pungency), and cardamom (which adds floral brightness). These pairings are fundamental to global spice blends—Indian garam masala, apple pie spice, and pumpkin pie spice all combine nutmeg with complementary warming spices.

Forbidden Pairings:

Nutmeg’s lack of acidity (sourness 1/10) means it resists pairing with bright, acidic dishes. Citrus-forward preparations, vinegar-based sauces, and tomato-based dishes clash with nutmeg’s profile—the spice disappears into acidity rather than integrating. Similarly, umami-dominant savory dishes without creamy or sweet elements can render nutmeg invisible or medicinal-tasting.

MEDICINAL DIMENSIONS: Beyond Culinary Pleasure

Nutmeg’s cultural significance extends far beyond flavor. For thousands of years, traditional medicine systems—from Ayurveda to Traditional Chinese Medicine to medieval European apothecaries—employed nutmeg for health support. Modern research validates many traditional uses while clarifying safe application ranges.

Antioxidant Properties:

Nutmeg is rich in phenolic compounds (protocatechuic, ferulic, and caffeic acids), flavonoids (particularly cyanidins), and essential oils that neutralize free radicals and protect cells from oxidative damage. This antioxidant capacity is comparable to many herbal supplements, though less concentrated than foods like blueberries or dark chocolate. Regular incorporation of nutmeg into meals contributes meaningful antioxidant intake supporting long-term cellular health.

Anti-inflammatory Effects:

The monoterpenes in nutmeg—particularly myristicin, eugenol, and safrole—demonstrate anti-inflammatory activity in research models. Studies show that nutmeg extract reduces inflammation markers and joint swelling in animal models. Traditional use for arthritis relief and joint pain appears supported by these mechanisms, though human clinical evidence remains limited. A pinch of nutmeg in mashed potatoes or creamy soup may offer gentle anti-inflammatory benefits as part of a broader healthy diet.

Antibacterial Activity:

Nutmeg demonstrates broad-spectrum antibacterial effects against oral pathogens (Streptococcus mutans, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis) that cause cavities and gum disease. It also inhibits harmful E. coli strains. These properties explain historical use in dentistry and support modern applications in natural dental products. The antibacterial activity suggests potential digestive benefits, though high-dose studies remain limited.

Digestive Support:

Traditional use in addressing digestive complaints—bloating, gas, indigestion—appears grounded in nutmeg’s antimicrobial properties and ability to stimulate digestive enzyme secretion. The antispasmodic effects may help relieve cramping and diarrhea. Clinical evidence is sparse, but incorporation of modest amounts (1/4 teaspoon) into warm milk or desserts may provide gentle digestive support.

Oral Health:

The eugenol content (shared with cloves) provides natural antimicrobial and anesthetic properties, explaining traditional use for toothaches. Modern oral care products increasingly incorporate nutmeg extract for anti-cavity and anti-gum-disease benefits.

Important Safety Consideration:

Nutmeg contains myristicin (13.57%), safrole (4.28%), and elemicin (1.42%)—compounds with psychoactive and hallucinogenic properties when consumed in large quantities. Normal culinary use (1/4 to 1/2 teaspoon) contains negligible amounts of these compounds and poses no health risk. However, consumption of 1 or more tablespoons (15-30 grams) of nutmeg can cause toxicity with symptoms including nausea, dizziness, numbness, and potentially seizures.

This is why nutmeg is designated GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe) by regulatory agencies at food-use levels while warnings exist about excessive consumption. For culinary purposes, use normal pinches and teaspoons—not tablespoons—and nutmeg becomes a beneficial ingredient without risk.

STORAGE AND PRESERVATION: Maintaining Maximum Potency

Proper nutmeg storage determines whether your investment yields months of aromatic joy or years of flat, medicinal disappointment.

Whole nutmeg seeds possess remarkable shelf life when protected from light, heat, and moisture. Stored in airtight glass containers in cool, dark conditions (50-60°F ideal, room temperature acceptable), whole seeds maintain flavor for 3-5 years, and can last even longer if stored perfectly. Because the essential oils remain protected within the seed coat, oxidation proceeds slowly. Test freshness by grating a pinch—fresh nutmeg releases intense, sweet aroma immediately.

Ground nutmeg faces far greater challenges. Upon grinding, the 6.85% essential oil (containing your 13.57% myristicin and other volatiles) is exposed to air over thousands of increased surface-area particles. Oxidation and volatile evaporation begin immediately. Ground nutmeg retains optimal flavor for approximately 6 months, though remains usable for 2-3 years if stored in airtight containers away from heat and light. The practical approach: purchase whole nutmeg, grind fresh for important preparations, but keep backup ground nutmeg for convenience. Replace ground nutmeg every 6 months for peak performance.

Storage location matters profoundly. Kitchen countertops near stoves (heat fluctuation), above dishwashers (moisture exposure), and under kitchen lights (light damage) all accelerate degradation. Ideal storage is a cool, dark pantry or spice cabinet in glass or metal airtight containers. Never refrigerate (moisture causes clumping and potential mold growth). Never store in plastic containers (nutmeg oils leach chemicals and cause container degradation).

To extend shelf life of ground nutmeg, consider purchasing a small nutmeg grater and whole seeds, grinding only what you’ll use within 72 hours. This requires minor extra effort but delivers flavor improvements that justify the investment for serious cooks.

SUBSTITUTION GUIDE: Alternatives When Nutmeg Isn’t Available

Despite nutmeg’s unique profile, several substitutes work in specific applications when the spice is unavailable.

Mace (Best Substitute, 1:1 Ratio):

Mace is the red aril surrounding the nutmeg seed—essentially the sister spice from the same fruit. It delivers similar warm, earthy, slightly sweet character but with more delicate, refined notes and slightly less heat. If you can source mace, it substitutes directly for nutmeg at equal amounts with minimal flavor shift. This is the closest match available.

Allspice (Excellent Substitute, 1:1 Ratio):

Made from dried berries of Pimenta dioica, allspice tastes like a blend of cinnamon, clove, and nutmeg—which makes it an excellent single substitute. Use allspice at 1:1 ratio in recipes calling for nutmeg, particularly in baked goods and sweet preparations.

Cinnamon (Good Substitute for Baking, 1/2 Amount):

Cinnamon provides warmth and sweetness but lacks nutmeg’s earthiness. When using cinnamon as a substitute, begin with half the nutmeg amount and adjust upward to taste. Combine cinnamon with a pinch of allspice or ginger for more complete flavor coverage.

Apple Pie Spice (Convenient Substitute, 1:1 Ratio):

This pre-blended mixture combines cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice, and ginger—making it a ready-made partial solution. However, it introduces additional spices not in the original recipe, so use judiciously.

Pumpkin Pie Spice (Convenient Substitute, 1:1 Ratio):

Similar to apple pie spice, this blend includes nutmeg plus cinnamon and ginger. Acceptable for baked goods but introduces flavor variations.

Ginger (Acceptable for Savory Dishes, 1:1 Ratio):

Ground ginger provides warmth and spice but shifts flavor profile toward pungency rather than earthiness. Use fresh ginger as nutmeg substitute in savory applications—curries, meat dishes, soups—at 1:1 ratio, though the flavor becomes distinctly different.

Star Anise (Acceptable for Beverages, 1:1 Ratio):

For drinks or slow-simmered applications, star anise provides sweet, licorice-forward warmth but lacks nutmeg’s earthiness. Better for mulled beverages than culinary dishes.

Cardamom (Strong Substitute, 1/2 Amount):

Green cardamom provides warm, slightly floral, citrus notes—a different profile than nutmeg but with pleasant warmth. Use 1/2 the nutmeg amount as cardamom is significantly more potent.

GLOBAL CUISINES: Nutmeg’s Cultural Expressions Across Continents

Nutmeg appears in virtually every culinary tradition, yet each culture deploys it distinctly. Italian Cuisine features nutmeg prominently in creamy béchamel sauce (made with butter, flour, and milk), which becomes the binding element in lasagna, ravioli, and filled pasta preparations. The classic ricotta filling for tortellini includes nutmeg as essential component.

Northern Italian risotto and creamy polenta preparations often finish with nutmeg’s warmth. The spice appears in Italian sausage mixtures, creating the warm undertone characteristic of authentic Italian sausages.

Indian Culinary Traditio

incorporates nutmeg into garam masala (the warm spice blend foundational to countless curries, rice preparations, and spiced dishes). Indian cooks understand nutmeg as a warmth provider—added to rich curries, biryani rice, and milk-based desserts. The spice also appears in Indian beverages, particularly spiced milk preparations and chai variations.

Middle Eastern Cooking

employs nutmeg in meat stews, particularly lamb preparations where its earthiness complements the protein’s richness. Middle Eastern spice blends featuring nutmeg, cinnamon, and other warming spices coat lamb kofta, create sophistication in slow-braised meat dishes, and appear in traditional mezze preparations. Nutmeg also seasons savory pies and meat-filled pastries throughout the Levantine region.

French Cuisine

considers nutmeg essential in classical béchamel sauce—the mother sauce of French cooking. Beyond béchamel, nutmeg appears in French soups (particularly vegetable creams), creamy pasta preparations, and comfort dishes like gratin dauphinoise. French pastry traditions incorporate nutmeg in certain sweetened preparations, though more sparingly than American baking.

Greek and Mediterranean Cooking

makes nutmeg essential in moussaka—the layered eggplant and meat dish bound together with béchamel sauce. Greek spice rubs for lamb and kofta preparations include nutmeg. The spice bridges Greek and Turkish culinary traditions, appearing in traditional meat-filled pastries and savory preparations.

American Baking Tradition

has made nutmeg synonymous with autumn—pumpkin pie, apple pie, spice cake, gingerbread, and holiday desserts all feature this spice as defining element. American comfort food traditions include nutmeg in mashed potatoes, sweet potatoes, and various vegetable preparations.

Caribbean Tradition

centers on Grenada, where nutmeg is not just a culinary ingredient but a national symbol appearing on the flag itself. The warm, spiced character of Caribbean cooking—influenced by African, Indian, and European traditions—incorporates nutmeg into meat dishes, rice preparations, and traditional preserves.

CONCLUSION

Nutmeg is not a seasonal spice but a fundamental culinary tool that bridges sweet and savory, simple and sophisticated, traditional and innovative. Understanding its chemistry (21.38% sabinene, 13.92% terpineol, 13.57% myristicin), mastering its applications (whole versus ground, raw versus toasted, blooming versus direct addition), and knowing its pairings (sweetness, cream, earthiness, complementary spices) transforms it from background seasoning into culinary superpower. Purchase whole nutmeg, invest in a microplane grater, toast seeds before grinding for important preparations, bloom ground nutmeg in butter for maximum distribution, store wisely in dark glass containers, and grate fresh moments before serving to maximize aroma—these simple practices elevate nutmeg from convenient pantry staple to transformative ingredient that transforms competent cooking into exceptional cuisine.